THE TRAVEL SECTION

Roads Not Taken

BY THOMAS SWICK

Why is so much travel writing so boring? Why on Monday morning do people talk about an op-ed piece they read in the Sunday paper, or a sports column, or a magazine essay, or a feature profile, but rarely a travel story? Why do the travel magazines, lavish with tips and sumptuous photographs, leave us feeling so empty? (Journalism's tiramisu.) Why has the travel book become a rich literary domain while the travel story has not?

One simple answer is that Travel is not a high priority at any newspaper. Like Food, Fashion, Home & Garden, it is far removed from the main business of reporting the news. Yet the Travel section has enormous potential precisely because of its life of low expectations. It need not adhere to the strictures of journalism that govern the rest of the newspaper -- brevity, clarity, distance; instead it can accommodate leisurely, nuanced, occasionally passionate writing. Because it is not the most important section of the paper -- quite the contrary -- it can experiment, take risks, have fun. It should -- by virtue of its generous space, deadlines, and subject matter -- feature the best writing in the newspaper.

But it's had its handicaps. In the old days Travel sections brimmed with florid passages of trumped-up delights, usually written by a recent guest of the hotel or island or tour being extolled. Then in the late 1980s a debate on ethics was launched, and many papers cut their ties with writers who took subsidized trips. This should have improved the sections, since many of the people cast out -- so called "professional travel writers" -- were free-loaders who had simply found a cheap way to travel.

But the trend had already shifted toward more service-oriented articles, telling readers where to stay and what to see and how to do it. Of course, Travel sections have to publish helpful information; it would be churlish of them not to. People come to them looking not only for ideas, but for ways and means. But a concentration on the practical to the exclusion of the evocative and ruminative discriminates against the large number of people who -- for various reasons -- don't travel. It ignores the fact that, in this day of disappearing foreign bureaus, the Travel section is many papers' only in-house window on the world at large. And it does a disservice to people who do travel by suggesting that this patently transportive act is nothing more than a series of negotiable transactions. (Not to mention the fact that the job of merely stockpiling information is now being done much better -- with greater timeliness and infinitely wider scope -- on the Internet.)

To serve their purposes, without appearing too utilitarian, newspapers have created a standard type of travel story that is generally about a person who goes to a place -- as opposed to being about a place -- often with a spouse or companion. In this genre, a variation on the phrase "my husband, Ken, and I," is pretty much de rigueur by at least the third paragraph. These two prim sojourners invariably stay in good hotels ("elegant" if in a city, "rustic" in the country), and eat in fine restaurants, savoring the "succulent regional cuisine." They visit the museums and other sights, which allows for the inclusion of pertinent historical facts, as well as helpful touristic information. "The following two days were packed with visits to Neapolis, the Greek theater, and the Latomia del Paradiso (an ancient quarry, now overgrown), never leaving us time to use the hotel's inviting private beach" (from a New York Times story by Ken's wife, last September).

The author may express to his or her companion admiration for ancient skills or practices, which, it is sometimes added, are sadly lacking today. They stroll cobblestone streets, palm-fringed beaches, hedgerowed lanes, patchwork fields (pick your picturesqueness); they drift blissfully through a "land of contrasts." Though sometimes baffled by strange money or foreign telephones, they are never in any danger. They leave enchanted and refreshed -- though rarely moved or permanently altered -- frequently vowing to return some day. It is the travel story's equivalent of living happily ever after, and it leaves a reader with the sense that something is missing in this fairy tale.

For starters, there's almost nothing negative. This is partly a vestige of the old days of free trips, when it was bad form to speak unfavorably of a place that had treated you lavishly. A tone of uncritical approval crept into travel journalism that has yet to be eradicated. Paul Theroux's famously sniping journeys are an obvious reaction against this rosiness, though his style, despite the enormous popularity of his books, has failed to make a dent in travel journalism.

The irony is that in their mission to "inform" their readers, Travel sections misinform them through their unrelenting good cheer. A few years ago I received a call from a woman who wished to express her despair at the large number of stray dogs she'd seen on a trip to Puerto Rico. Her complaint was against the island, but implicit in it was an indictment of travel journalism, for nothing she had read about Puerto Rico had prepared her for abandoned animals.

Joining the "negative" in the travel story's closet of unmentionables is a sense of the present. It is not that the stories are timeless, but rather that their preferred frame of reference is the past.

The narrators of conventional travel stories tend to be interested only in history; if the present intrudes in their stories at all it does so in the ephemeral and nugatory realm of the trendy: the latest restaurants, the hottest clubs. But during the day, their work hours, they dutifully visit the museums, the landmarks, the churches, the battlefields; they ignore the everyday life of the streets. Which is why when you read about Puerto Rico you hear all about the colonial architecture of old San Juan and nothing about the population of stray dogs.

A knowledge of the past is, of course, essential to an understanding of the present. And the past is easy: it is housed, displayed, labeled (often in English), accessible. The present is fluid, inchoate, and often unintelligible. It is an unknown quantity. History books, guidebooks, travel stories have all told us the lessons of yesteryear; the challenge and thrill of travel is discovering those of today. And we find them in the streets and the parks, in cafes and stadiums, in offices and homes. Some of these places are difficult to gain access to, but that is precisely the point: anyone can see a painting; it is a rare and invaluable privilege to get invited in for a meal. It is this distinction -- how you travel, not where -- that defines a traveler as opposed to a tourist. And it is the job of travel writers to have experiences that are beyond the realm of the average tourist, to go beneath the surface, and then to write interestingly of what they find.

One way to accomplish the latter is to employ the third element missing from the conventional travel story: imagination. Most travel journalists are under the impression that since they are writing nonfiction -- and travel nonfiction at that --they need only record what is there (and, as we have seen, not all of that). Yet all writing is enhanced by a creative imagination. To illustrate, I present the lead from a New York Times travel story, dated September 3, 2000. (Though not the one by Ken's wife.)

"Just my luck," I muttered, gazing at the unattended welcome sign to Lassen Volcanic National Park in Northern California. "STOP. Pay $10 here," it said. All I had was a $20 bill.

Compare that with this lead, from a story by Peter Ackroyd, which appears in Views from Abroad, a collection of travel writing from the London Spectator:

Each Nordic country is cold in its own way; in Oslo, it is a rural cold, the cold of surrounding landscape. An urban cold rises from Stockholm, from the streets and public buildings. In Helsinki it is an elemental cold, a cold which invades the body and leaves it stunned. At midday you gaze at the sun without blinking; all things turn to ice. It is like the coldness of God. To travel here from Sweden is to move from light sleep to a harsh and sudden consciousness.

Ackroyd's imaginative sense -- aside from keeping us spellbound -- leads to insight, which is the fourth element missing from the conventional travel story. Good travel writers understand that times have changed, and in an age when everybody has been everywhere (and when there is a Travel Channel for those who haven't), it is not enough simply to describe a landscape, you must now interpret it.

Jonathan Raban, writing about the Mississippi River floods in Granta a few years back, opened with this show-stopping sentence: "Flying to Minneapolis from the West, you see it as a theological problem." He went on to describe "this right-angled, right-thinking Lutheran country" and the "deviously winding" Mississippi River, which "looks as if it had been put here to teach the God-fearing Midwest a lesson about stubborn and unregenerate nature." Just as travel sections have become more practical, travel books have become more analytical.

Read enough stories with sentences beginning "Just my luck" and "My husband, Ken, and I" and you soon discover the fifth element that is too often absent from the conventional travel story: humor. Occasionally, you will find pieces by writers with a light, amusing style, but the humor is almost always directed at themselves -- the innocent fumblings of the fish out of water. Its sole purpose is to get a laugh, not to reveal interesting truths about national character.

The emergence of humor is handicapped by the absence of dialogue (missing element #6). In recent times, writers of travel books have gone to the most sparsely populated regions -- Patagonia (Bruce Chatwin) and Siberia (Colin Thubron) -- and come back with pages of scintillating dialogue. Even the misanthropic V.S. Naipaul stoops to talk to the locals. Yet in the conventional travel story, no one speaks; reading it is like moving through a landscape of mimes -- figures are sensed, sometimes even seen, but almost never heard from.

The absence of dialogue is directly related to the omission of the final and most important element: people. Except for the author and his or her companion, few characters ever clutter the stage of the conventional travel story. Travel journalists may go to the most densely populated cities in the world -- Tokyo, Cairo, Mumbai; places where you are immersed in a crush of humanity -- and fail to introduce their readers to a single human being. In the history of travel journalism, more has been written about the animals of Africa than the people.

And the question lingers: What can you know -- and feel -- about a place when you don't meet the people who live in it? We learn through human contact, and the knowledge that we gain is of infinitely greater value than any number of practical tips. Similarly, it is through human contact that we open our hearts. Enlightenment and love -- there are no more compelling reasons to travel, or write about it.

Thomas Swick is the travel editor of the South Florida Sun-Sentinel and the author of the travel memoir Unquiet Days: At Home in Poland.

Tuesday, September 28, 2004

Travel Writers as Freeloaders

Travel writers often turn a blind eye to reality

Today is the debut of a media column by National Golf Editor Tim McDonald. The column will take a broad look at some of the ills of travel journalism, and future monthly columns will take a look at both the good and bad in the world of golf media, both in print and broadcast.

(Sept. 2, 2004) – In journalism, there should be a note of skepticism between the writer and the source. Human sources often have agendas, sometimes hidden, sometimes in plain view.

One of the jobs of the journalist is to determine whether the source is trustworthy enough to override the natural skepticism. It’s an ongoing war, one that reputable reporters deal with constantly. There is one genre of journalism, however, that doesn’t seem to understand there is a war going on.

Not only do many travel writers seem oblivious of this conflict, or willfully ignorant of it, they too often consort with the enemy. In nearly a quarter century in journalism, I have never witnessed such a chummy, journalistic relationship as the one that exists between most travel writers and the big, hungry PR machine.

Free trips and goodies

It seems all the PR people have to do is dangle a free trip and goodies in front of a travel writer and they are assured of glowing reviews. Most good reporters treat public relations people politely, because PR people can be good sources of information, even if that information is necessarily one-sided. Most reporters also know to take PR people with a grain of salt: the PR person’s very job is to "sell" the writer on whatever product, destination or service he or she has been hired by.

Travel writers too often treat PR people as ultimate sources. This is great – and easy – for the PR person and the travel writer, but, of course, the reader suffers because he or she is getting misinformation or, at the very least, incomplete information.

Travel writing as a whole has gone downhill over the last quarter century. An ethical debate grew in the 1980s over this very subject, with many newspapers axing writers who accepted subsidized press trips.

Still, not much has changed.

"Bad form" to criticize. "For starters, there’s almost nothing negative," South Florida Sun Sentinel travel editor Thomas Swick wrote in The Columbia Journalism Review. "This is partly a vestige of the old days of free trips when it was bad form to speak unfavorably of a place that had treated you lavishly."

Swick also wrote: "A tone of uncritical approval crept into travel journalism that has yet to be eradicated...The irony is that in their mission to "inform" their readers, travel sections misinform them through their unrelenting good cheer."

Swick noted most travel writing is of the first-person variety and usually involves a traveling companion, spouse or friend. "These two prim sojourners invariably stay in good hotels (‘elegant’ if in a city, ‘rustic’ in the country)," he wrote. "And eat in fine restaurants savoring the ‘succulent regional cuisine.’ "

It’s even worse in travel magazines, both online and in print.

Mmmm, good. A random review of 50 online stories by 19 freelance travel writers, all members of the Society of American Travel Writers, found precious little "negative reporting." You want "unrelenting good cheer," find your local freelance travel writer.

A small sampling:

"Soon a silver tray with coffee and a glass of iced water, always served here with coffee, and the famous chocolate torte was set before me," wrote SATW member Tess Bridgwater about a visit to Vienna. "Does it deserve its reputation? The answer is Mmm."

Freelance travel writers who specialize in the Caribbean seem to be particularly guilty. This is partly because the Caribbean is such a great place to freeload, and partly because the Caribbean, so dependent on tourism, aggressively woos travel writers.

In 2004, travel and tourism in the Caribbean is forecast to generate $40.3 billion in economic activity, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council.

"Travel and tourism is without question the most important export sector in the region," WTTC president Jean-Claude Baumgarten said at a June 2004 conference. "It helps to diversify the Caribbean economy, stimulate entrepreneurship, catalyze investment, create sustainable jobs and helps development in local communities."

Awards to colleagues

The Caribbean Hotel Association even hands out awards to members of the media who CHA members feel "foster excellence in tourism reporting in the Caribbean."

It may come as no surprise the winners almost unfailingly put the Caribbean in a good light.

For example, Mark Meredith, one of the recent winners, wrote a story on the Asa Wright Nature Center under the headline: "Promoting Trinidad and Tobago."

Even non-winners are almost overwhelming in their "unrelenting good cheer."

What about the seedy side?

For example, Brenda Fine, another SATW member, wrote for bridalguide.com: "Who knew a tropical island could be so worldly? Islands in the Caribbean - aside from being superlatively romantic - are a mini-United Nations, each has its own mix of cultures blended into the island traditions. Immerse yourselves in Dutch, Spanish, English Scandinavian or French customs and food while you enjoy the bliss of a tropical paradise – the best of both worlds."

Or SATW member Barbara Radin Fox, with Larry Fox, on Miami, for romanticgetaways.com: "In this sun-kissed paradise, the center of action is South Beach, which has it all: a long and wide beach, beautiful hotels, excellent restaurants, and neon-lit streets that pulsate with Latin and rock rhythms."

A typical, if cliched, description of South Beach, but not a word of the 369 crimes committed on South Beach in 2003, including rape, robbery, felony assaults, auto theft and burglaries. Isn’t that something you might want to know if you were planning a trip to South Beach?

Don’t spoil a good thing

So why rock the boat? It’s a good life, with free trips to exotic places, and free food at great restaurants.

"Are you itching to break into the glamorous world of travel writing," reads a come-on from freelancetravelwriters.com. "To see your name in glossy print and receive regular invitations for fabulous VIP press trips that cost you only the taxi fare to the airport?"

In today’s economic climate, any number of publications are forced to accept subsidized trips – including TravelGolf.com – if they want to produce travel stories for readers.

But it doesn’t necessarily follow that the resulting stories must be unrelentingly cheerful. We here at TravelGolf.com have been guilty of that in the past, and are working to be more objective and critical.

It may not always work – and we are sure to alienate some powerful PR moguls – but in the end, we want readers to have a place to come for good, objective reviews of places to go and golf courses to play.

One last word from Swick: "Why do the travel magazines, lavish with tips and sumptuous photographs, leave us feeling so empty?"

Hopefully, you’ll be able to read TravelGolf.com and not feel that way.

The opinions expressed above are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of TravelGolf.com management.

Comment on this story on our reader feedback page.

The information in this story was accurate at the time of publication. All contact information, directions and prices should be confirmed directly with the golf course or resort before making reservations and/or travel plans

Today is the debut of a media column by National Golf Editor Tim McDonald. The column will take a broad look at some of the ills of travel journalism, and future monthly columns will take a look at both the good and bad in the world of golf media, both in print and broadcast.

(Sept. 2, 2004) – In journalism, there should be a note of skepticism between the writer and the source. Human sources often have agendas, sometimes hidden, sometimes in plain view.

One of the jobs of the journalist is to determine whether the source is trustworthy enough to override the natural skepticism. It’s an ongoing war, one that reputable reporters deal with constantly. There is one genre of journalism, however, that doesn’t seem to understand there is a war going on.

Not only do many travel writers seem oblivious of this conflict, or willfully ignorant of it, they too often consort with the enemy. In nearly a quarter century in journalism, I have never witnessed such a chummy, journalistic relationship as the one that exists between most travel writers and the big, hungry PR machine.

Free trips and goodies

It seems all the PR people have to do is dangle a free trip and goodies in front of a travel writer and they are assured of glowing reviews. Most good reporters treat public relations people politely, because PR people can be good sources of information, even if that information is necessarily one-sided. Most reporters also know to take PR people with a grain of salt: the PR person’s very job is to "sell" the writer on whatever product, destination or service he or she has been hired by.

Travel writers too often treat PR people as ultimate sources. This is great – and easy – for the PR person and the travel writer, but, of course, the reader suffers because he or she is getting misinformation or, at the very least, incomplete information.

Travel writing as a whole has gone downhill over the last quarter century. An ethical debate grew in the 1980s over this very subject, with many newspapers axing writers who accepted subsidized press trips.

Still, not much has changed.

"Bad form" to criticize. "For starters, there’s almost nothing negative," South Florida Sun Sentinel travel editor Thomas Swick wrote in The Columbia Journalism Review. "This is partly a vestige of the old days of free trips when it was bad form to speak unfavorably of a place that had treated you lavishly."

Swick also wrote: "A tone of uncritical approval crept into travel journalism that has yet to be eradicated...The irony is that in their mission to "inform" their readers, travel sections misinform them through their unrelenting good cheer."

Swick noted most travel writing is of the first-person variety and usually involves a traveling companion, spouse or friend. "These two prim sojourners invariably stay in good hotels (‘elegant’ if in a city, ‘rustic’ in the country)," he wrote. "And eat in fine restaurants savoring the ‘succulent regional cuisine.’ "

It’s even worse in travel magazines, both online and in print.

Mmmm, good. A random review of 50 online stories by 19 freelance travel writers, all members of the Society of American Travel Writers, found precious little "negative reporting." You want "unrelenting good cheer," find your local freelance travel writer.

A small sampling:

"Soon a silver tray with coffee and a glass of iced water, always served here with coffee, and the famous chocolate torte was set before me," wrote SATW member Tess Bridgwater about a visit to Vienna. "Does it deserve its reputation? The answer is Mmm."

Freelance travel writers who specialize in the Caribbean seem to be particularly guilty. This is partly because the Caribbean is such a great place to freeload, and partly because the Caribbean, so dependent on tourism, aggressively woos travel writers.

In 2004, travel and tourism in the Caribbean is forecast to generate $40.3 billion in economic activity, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council.

"Travel and tourism is without question the most important export sector in the region," WTTC president Jean-Claude Baumgarten said at a June 2004 conference. "It helps to diversify the Caribbean economy, stimulate entrepreneurship, catalyze investment, create sustainable jobs and helps development in local communities."

Awards to colleagues

The Caribbean Hotel Association even hands out awards to members of the media who CHA members feel "foster excellence in tourism reporting in the Caribbean."

It may come as no surprise the winners almost unfailingly put the Caribbean in a good light.

For example, Mark Meredith, one of the recent winners, wrote a story on the Asa Wright Nature Center under the headline: "Promoting Trinidad and Tobago."

Even non-winners are almost overwhelming in their "unrelenting good cheer."

What about the seedy side?

For example, Brenda Fine, another SATW member, wrote for bridalguide.com: "Who knew a tropical island could be so worldly? Islands in the Caribbean - aside from being superlatively romantic - are a mini-United Nations, each has its own mix of cultures blended into the island traditions. Immerse yourselves in Dutch, Spanish, English Scandinavian or French customs and food while you enjoy the bliss of a tropical paradise – the best of both worlds."

Or SATW member Barbara Radin Fox, with Larry Fox, on Miami, for romanticgetaways.com: "In this sun-kissed paradise, the center of action is South Beach, which has it all: a long and wide beach, beautiful hotels, excellent restaurants, and neon-lit streets that pulsate with Latin and rock rhythms."

A typical, if cliched, description of South Beach, but not a word of the 369 crimes committed on South Beach in 2003, including rape, robbery, felony assaults, auto theft and burglaries. Isn’t that something you might want to know if you were planning a trip to South Beach?

Don’t spoil a good thing

So why rock the boat? It’s a good life, with free trips to exotic places, and free food at great restaurants.

"Are you itching to break into the glamorous world of travel writing," reads a come-on from freelancetravelwriters.com. "To see your name in glossy print and receive regular invitations for fabulous VIP press trips that cost you only the taxi fare to the airport?"

In today’s economic climate, any number of publications are forced to accept subsidized trips – including TravelGolf.com – if they want to produce travel stories for readers.

But it doesn’t necessarily follow that the resulting stories must be unrelentingly cheerful. We here at TravelGolf.com have been guilty of that in the past, and are working to be more objective and critical.

It may not always work – and we are sure to alienate some powerful PR moguls – but in the end, we want readers to have a place to come for good, objective reviews of places to go and golf courses to play.

One last word from Swick: "Why do the travel magazines, lavish with tips and sumptuous photographs, leave us feeling so empty?"

Hopefully, you’ll be able to read TravelGolf.com and not feel that way.

The opinions expressed above are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of TravelGolf.com management.

Comment on this story on our reader feedback page.

The information in this story was accurate at the time of publication. All contact information, directions and prices should be confirmed directly with the golf course or resort before making reservations and/or travel plans

Friday, September 24, 2004

Will You Get Ahead with Internship?

Travel Writer Tours Sukhothai

Internal Bleed

Our outgoing editorial intern wonders if he'll ever get a real job.

By Greg Bloom – September 8, 2004

I worked for mediabistro.com all summer, but I didn't get paid for it. My only payment, really, is the opportunity to write this—and things like it—for free. You see, I am a member of a growing class of unrepresented, unprotected, arguably illegal laborers in this country: I'm an intern. I have few rights, less accountability, and only the occasional, odd-job paycheck. Hell, I can't claim even to be an intern anymore—my time at mediabistro.com, sweet as it has been, just ended. And now, well, at least I can quit lying to myself and my loved ones and answer truthfully when people ask what I do. It is a great weight off my chest that I can simply grimace and say, "I'm unemployed."

It wasn't supposed to be this way.

I did what you're expected to do when you're an overambitious, overeducated kid: I started interning when I was in college. The idea is that the intern gains practical experience and real-world connections. You do one or two, and you're well on your way to a real job upon graduation. At least that's what they want you to think. And back when I was still a wide-eyed undergrad, I believed it.

I was pleased when I tripped into my first internship. After class one day, my journalism professor offered me a spot at the alumni magazine he edited, and, aw shucks, I took it. It wasn't Harper's, but I'd gain a place in which to escape the heat of a North Carolina summer for a few hours a day. I spent my summer compiling long lists of marriages, promotions, and deaths into the alumni record. It wasn't a bad gig—there was even some pay—but it wasn't quite what I'd been hoping for. My professor-cum-editor had shown our class all sorts of famous magazine journalism—Talese, Wolfe, Thompson.

I was primed to be working on a magazine staff, ready to play the game. So when I burst into the magazine office a month into the gig with a brilliant investigative pitch—the university had so-called deans on staff whose main function was to organize and recruit freshmen for Bible study—I was amazed when my editor mumbled only that maybe I could do a small calendar item about various religious events on campus. Then he handed me a fresh stack of obituaries to file. Apparently, an alumni magazine is not an appropriate medium for reporting of any particularly investigative nature, especially about the university itself.

But I'd learned something important: That journalism isn't all Woodward and Bernstein. And when the summer ended and I was offered a job there, writing profiles and covering events like Homecoming, I respectfully declined and realized I'd learned something even more important. If you're not interested in getting an actual job at the place of your pseudo-employment, the whole thing really does you no good. The best possible outcome is a bullet on your resume—and maybe a reference.

One internship does not a resume make, and so I tried to find more unpaid work, this time something closer to my interests. The alumni-mag editor introduced me to a young, rising star in the mag world, a man who had gotten his own glossy publication onto newsstands internationally yet was hardly out of his twenties. He and his girlfriend had scrapped and saved and raised capital and ran it all themselves; he edited, she designed.

I instantly had two new role models. They said they needed a third hand, "for everything else." I welled with excitement at the thought of all the other poor lowly interns filing, labeling, taking messages for assistants to associates at massive corporations—this time, I thought, I could really get myself into something worthwhile.

The magazine had pretty pictures. I should have stopped to actually read it. There were lots of poems about dark, smoke-filled cafes and old black men. There were photo essays about graffiti. There were calendars that listed the dates of "world beat" music festivals. There was a 5,000-word essay about Budapest, written entirely in the third person and referring to that protagonist only as "the poet," but without providing any salient historic or logistical information about the city. Once I started working, one of my few tasks was to answer the phone and generally deflect the callers.

Frequently, I had to deflect the publisher, who once, in great seething understatement, inquired why there was a typo the magazine's cover. And typos throughout the inside, too. It turned out that without much of a budget, the editor had written and edited most everything himself. (Which meant he was the obtuse "poet.") And thus I learned my third lesson: Even if things weren't going quite so horribly here, it was ultimately another dead end. A shoestring operation wasn't hiring anyone any time soon, so the best result I could hope for was another reference.

Now I was confident. I had two internships under my belt, so I could proceed to a real job. Right? Um, no. In fact, this is when I finally realized that I'd been duped, that millions of my peers were duped. As I glanced through mediabistro.com one day, I could see that entry-level job postings always fell into two categories: either internships or positions requiring a year or two of professional experience. This was the elephant-sized hole in the job market's living room, a yawping gap in the ladder between the intern's rung and the ground level of real employment.

So I started asking around to see how people had done it. My suspicions were confirmed. Barring deus ex masthead—someone in the right rung moves, gets pregnant, or is struck by various forms of career lightning—an internship won't land you a job; if the timing doesn't come up in your favor, it's just back to waiting in line. Sure, your performance in the internship makes a big difference, but once the stint is over, it all gets lost behind just another bullet in the resume.

I obediently stepped back into line. I knew someone who knew someone who knew the mediabistro.com folks, and, I figured, where better to finally find a media job than at a site all about media jobs?

I must first say that of all my pseudo-employers, mediabistro.com was the best. The nice thing about this place is that the folks here make the industry—which at times can seem irrational, baseless, and fickle—seem engaging, easygoing, and infinitely entertaining. What's more, they know that even though hard work and merit badges don't quite equal success in these fields, it doesn't mean that there aren't proven formulas for getting ahead. In that way, they are a perfect place for a media internship. But it's also a small operation, not quite shoestring anymore, but not much bigger. I was ignoring my third rule. But I was also enjoying it.

One of my first assignments here was to contact successful media professionals and ask them about their own internship experience. The project didn't get very far. Turns out that internships haven't ignited too many great careers, at least not yet. Most people who have weathered the internship in its modern sense are still on the mild slope of the career curve.

Back in the day, it seems, people just got low level jobs, in the mailroom or on the switchboard—much like internships, they're small jobs for people with underdeveloped skill sets, but with significant differences. For one, there's a paycheck—often with a side dish of health coverage—but more, important, you have real responsibilities, however minor they may be.

Now that college degrees are nearly universal and companies have learned to take advantage of this naïve and expendable free labor, internships are less like apprenticeships and more like unpaid temp jobs. There's rarely any hope of advancement, and all the burden of proof is on the intern. Employers aren't looking to help you improve; they're keeping you around to have someone trained in case an employee leaves. No amount of hard work can change that—in fact, as mb editor-in-chief Jesse Oxfeld delights in telling me, the biggest mistake I made here was proving to be an excellent transcriber. It didn't get me a job; it just brought me more transcribing.

I'm not complaining about that. Really. I realize that I'm in an extremely fortunate position: I might still be treading water two years after graduation, but I'm not afraid of actually drowning. Make no mistake—a summer or three living in expensive cities while working for no pay is a luxury, and this shows in the people who end up doing it. When I flip through my graduating class's facebook, I notice that those with the most high-profile internships are the ones for whom a wageless summer living in an East Village loft is not much of a concern. We're not climbing a ladder; we're riding an escalator. As a result, the younger generation comes from narrower backgrounds and has a more limited range of experiences. We're more willing to pay dues, no matter how degrading, but we're less inclined to be innovative and take risks.

This whole system isn't good for the interns, and it can't be good for the industry either. It's creating a limited talent pool, and, beyond that, a company gets only what it pays for: a constantly changing bottom floor filled with people who have little or no vested interest in business performance, sucking up bandwidths, writing potentially embarrassing emails, engaging in scandalous interoffice behavior, without having a real job to worry about losing. How long will it be before the internship inefficiency becomes acknowledged and eliminated?

Of the few things I've learned from internships, their central lesson is still a vital one for a spoiled college grad with a throbbing sense of entitlement: until fate finds you or you find fate, you ain't shit. That's a lesson I can get behind. But if I keep learning it, the stench will be intolerable.

Greg Bloom is a former editorial intern at mediabistro.com who has left the magazine industry for the moment. He is currently trying to save the world.

The Perils of Internship

Declining Pay for Freelance Writers

Travel Writer at Pyramids

Getting It Write

With per-word rates shrinking and salaries sinking, our freelancer rethinks how she measures success.

By Kristen Kemp – September 22, 2004

In the fiscal year 2000, I made $77,000. I didn't pimp myself out (in the literal sense), and I didn't get in on Martha Stewart's IPO. I just freelanced. I wrote more magazine articles than I can remember. I had a contract for a series of four kids' novels. I was paid $800 for two days of speaking at a public elementary school. Those days, fees were hot, and anyone with a semi-important job title was looking to hire a hack. As a result, my scrappy lifestyle went upscale. I visited the Bliss Spa twice (and no one had given me a gift certificate!). I traded my cheap chain restaurants for the ones they show on the Food Network. I bought a Bichon Frise and upgraded to Ketel One. I spent a lot of time writing and hustling, sure. But what I remember most is how much time I spent playing.

Now it's September 2004, and I'm balancing my checkbook. I have $500 dollars left. The money is trickling in at the drip-drip pace of an IV tube. I have no book contracts, and invitations to speak are nonpaying. This year's calendar definitely doesn't include appointments at Bliss. But it's not just the money that's scarce—it's my time. I work harder and more diligently and more skillfully than I did in 2000. I spin my wheels pitching and turning in copy and taking on kooky tasks (I write advertorial letters that go out to stores' credit card holders). The buzz phrase for those of us with middle-class jobs right now is work more for less. Secretly, I still hope for a raise.

But it ain't gonna happen.

Let me set the record straight: I'm not complaining. Last year, I earned upwards of $40,000. For a freelance writer, that's OK. It's not $75,000, but it's not $20,000 either (which is a sum I've been familiar with in the past—that's the no cable, no Blockbuster, no fun range.) Last year, I carried a debt on my credit card, and I ate at Teriyaki Boy, but at least I could afford a few plane tickets. Life isn't luxurious, but it certainly isn't bad. I mean, how can I complain? I stretch the budget to add DVR to my cable, and I can spring for the better health insurance—the one that includes appointments with my shrink.

The bone that does beg to be picked is the one with the workload. Magazines and newspapers are under budget constraints, same as everyone. For this, I could blame the economy, the Republicans, or the pizza delivery boy. It doesn't matter who's at fault; things are still the same: I turn in story after story, complete edit after edit, and crank out ideas and revises. But I'm not getting raises for work that I'm told is well done; I'm getting salary cuts. One editor at a major magazine—a cool woman I've worked with for years—felt badly when she recently told me: "I want you to know that we aren't paying $2 a word anymore. We have to pay $1 to $1.50. Is it OK for me to still put your name in the hat for this story?" Of course it's OK. I'm happy to work for her, and I don't blame her for my mid-40s salary. After all, a smaller freelance budget at her magazine means she'll be spending longer hours at her office doing the writing she used to pay me to do.

I wonder what good it does for all of us middle- to upper-middle class folks to sit around feeling sorry for each other. Some writers—even the good ones—aren't getting much more than $.50 a word. But still, I gripe to my freelance friends—scrappy troopers scattered across the country from Park Slope to Hollywood—and they're having the same experience as me. "I'm still getting $2 a word, but I'm getting screwed on the word count," one says. "If they assign me a story for 1,500 words, then they'll ask for 2,000, end up running 1,800, and I won't get paid for the extra."

She's right. Four years ago, 1,000- and 2,000-word assignments at $2 per word were the standard at major publications. Now I get 800 to 1,000 word counts at $1.50 per word or less. That's not an economic slump; that's a new standard. Two other writers admit that they're taking smaller assignments for less money. They're afraid if they don't, they'll price themselves out and lose work. Another freelancer explains the current situation best: "There are so many newbie freelancers and freshly unemployeds who are willing to work for so little and do so much that seasoned freelance writers are competing with glorified interns for the steady, if not most satisfying, jobs."

You said it, sister.

I started in the magazine business in 1996, and I made $1 per word straight out of Indiana University Journalism School. (This is the rate writers have been paid since the 1960s.) One of the freelancers quoted above—five years more accomplished than me—advised me to start demanding more money in 1998. I did, and I wound up with a fat yearly income. Now, we're both taking whatever we can get. We aren't demanding. We are yes-women.

But even though our salaries have sunk and our playtimes are less playful, things are OK. She ended up taking a fulltime job and uses her freelance work as an income supplement. I'm starting to teach more writing classes so money will be steady and predictable, though hardly what I'd call abundant. Other freelance friends have taught dance classes, gone to grad school to get medical degrees, or taken corporate PR jobs. Most of us have some form of income supplement, and that's how we stay in the freelance game.

I've just accepted that the workload is going to be heavier. Who cares? I still love my job. I've downgraded to Stoli, but at least I can drink it at two o'clock in the afternoon (even though I don't). I can flip on the TV while I sit on my couch and work with the dog's nose propped next to my keyboard. I may not have the playtime—or the extra cash to make playtime more fun—but I still have the best job for me. I can't imagine life without freelancing, and I can't imagine that I'll ever stop complaining about it. I've mentally signed up for the duration, which means I'll write till the skin wears off my fingers. Who knows? One day—maybe in 2014—I'll see that raise.

Anything can happen, right?

Kristen Kemp is a freelance writer living in New York City. You can read her other "Getting It Write" columns in the archives.

Falling Pay for Freelance Writers

Thursday, September 9, 2004

The Lousy Pay For Freelance Writers

Moorish Man

Writers Weekly on Lousy Pay for Freelance Writers from Other Freelance Writers

September 08, 2004

To Pay or Not to Pay...Fellow Writers By A Struggling Freelance Writer

With keen interest I read a letter written to Angela Hoy from a fledgling newsletter editor unable to pay column writers. Angela nicely but firmly advised the editor to think twice about that no-pay policy. She warned the novice that the seasoned and veteran writers would flame viciously and ruin the editor's reputation.

Not so. Writers write for free all the time and no one seems to care. Writers even write for other writers without the respect of a paycheck. What I've learned as a writer who likes to write articles about writing, is that writers are some of the worse paymasters in the world. And for some reason that depresses me. But the irony continues to thrive.

Writers complain about the insult of little or no pay for their talent, but when the shoe is on the other foot and they evolve into editors and ezine/website owners, the concept of paying a writer becomes foreign if not totally forgotten. As they sell their own wares, they take from their own. At the risk of sounding harsh, is this not a bit cannibalistic?

With a deep breath and heavy heart, I did some research into the pay rates of online writing magazines to see if my gut was right. When I mentioned to Angela what I found, she asked if I'd be willing to divulge the findings. The review of a few well-known writing sites revealed the following information, which lists title, website, word length, and current pay rate to its contributing writers.

EZine Websites That Pay Freelance Writers

The list is ranked based on payment per word.

Writers Weekly.com $50 for ~600 words (8.3 cents/word); $30 for success stories of ~300 words (10 cents/word)

FundsforWriters $30 for 500-700 words (4-6 cents/word)

Writing World $40-$75 for 800-1500 words (5 cents/word)

KT Publishing $50 for ~1000 words (5 cents/word)

Write From Home $25 for 500-1500 words (1.6 - 5 cents/word)

Every Writer $20-40 for 500-2500 words (1.6 - 4 cents/word)

The New Writer £20 ($36) for 1000 words (3.6 cents/word)

Writing for Dollars $15-25 for 500-1000 words (2.5 – 3 cents/word)

Worldwide Freelance $20 for ~1000 words (2 cents/word)

Writing, Etc. $10 for 500-1000 words (1-2 cents/word)

National Association of Women Writers $10-20 for 600-1500 words (1.3-1.6 cents/word)

Writers Life $10 for 800-1500 words ($0.007 – $0.013 cent/word)

Fiction Factor $5 for 800-1200 words ($0.0042 - 0.0063 cents/word)

Absolute Write $5 for 800-2000 words ($0.0025 - 0.0063 cents/word)

EZine Websites That Don't Pay Their Freelance Writers

These are confirmed paying ezines. So many others continue to say "we are a non-paying magazine, but as we grow we hope to be able to pay our writers." At the same time, many of these ezines sell books, display affiliates, and offer courses demonstrating they do earn an income from which they could pay writers. Some examples of these sites are:

Writer Online: Pays zero to $50 for 100-5000 words (0-2 cents/word). We're putting this in the non-paying category because they only pay for "selected content." But, they don't tell you what that selected content is in their guidelines.

Writers Write: "The IWJ does not offer monetary payment at this time."

Fiction Addiction: "Fiction Addiction.NET is not currently a paying market."

Writer Gazette: No pay.

Working Writer: They want writers to pay for a subscription...but they don't writers.

Apollo's Lyre: "Apollo's Lyre is a non-paying market at the moment."

Writer's Crossing: "I can't pay you."

Author Mania: No pay.

Newsletters and ezines for writers are not unique in offering little or no pay for contributors. Ezine editors in all trades pay less for bytes than ink on paper. But in these days where writers fight to have paper editors compensate them separately for electronic rights, why do we as writers slight each other and dodge paying our own kind for those same rights?

We unite to fight the big editor but fail to emulate what we strive for – respect for our words in any format. Many non-paying editors say they can't afford to pay writers, yet ads appear on many non-paying sites. In response to an editor seeking writers for no pay, WritersWeekly.com's Angela Hoy said, "If you can't pay writers, perhaps you should find another line of business. It never ceases to amaze me how many people start these little newsletters and websites with no money to pay their initial bills. You can't start a business without money and expect it to survive, nor expect to offer a high-quality publication. It's like asking people to support your pipe-dream, which is incredibly selfish and unfair to new writers who don't know any better."

Why don't editors write their own material until they have the resources to pay columnists or use free, canned articles given away for press and book sales? A few do, but most do not.

Two reasons.

First, the editors must use their time to earn a living, usually writing, and don't have enough extra time to write free articles. Second, the canned articles show up in multiple places making them old news, defeating the effort to be fresh and different from the competition. So once again, while many editors are trying to make money, they deny it to their cohorts.

No, I do not believe malicious intent is represented here. Most of these editors genuinely originated their publications to aid their friends in the craft. I believe it's a cycle and a rut. It's hard to take on a new business expense when free seems to work just as well. And writers submit their work for free for various reasons such as collecting clips, free advertising (versus purchasing ad space), and the instant gratification of a byline (quite a temptation indeed).

And if the offer presents itself, an editor is going to use it. A good article for free is like finding a dollar on the street. Who can pass it up?The point I would like to make is that editors should do the right thing by their peers. Considered more experienced and knowledgeable, editors should step up to the plate and offer payment to writers, even if only a token amount. By paying a writer, the editor raises the bar of the writing environment. As the editor's success climbs, so should the compensation to the writers that helped him or her step up that ladder.

When times are lean, editors should write their own material. When times are fruitful, editors should reward writers appropriately.Allow a writer to at least earn money toward a website, DSL connection, or printer ink by paying for a piece. Selling several of those in a month might make a novice but talented writer feel prouder and more motivated to continue.

Writing for free makes the business only a hobby. To take it seriously, money needs to change hands. There is something about getting what you pay for that makes the whole profession, including these publications, more credible in the eyes of the editors, the writers, and the readers who are the customers for our words.

Copyright © 1997 - 2004 WritersWeekly.com. All rights reserved.

Sunday, September 5, 2004

Guidebook Contract Offer

Concorde Final Flight

Tom Brosnahan

Guidebook Contract Offer

I received a message from "Mexico Mike" Nelson, an author specializing on Mexico, asking my opinion of a book deal he had been offered. His questions and the responses might be helpful to other authors.

Tom, perhaps you'd be willing to help me with a good "problem". I've been offered a chance to do a book on Mexico (a travel guide) by [a travel guide series]. They have guides to Hawaii, Australia and that part of the world, but nothing on Mexico. I'd be starting from scratch. Length is to be 300-500 pages. They offered me a royalty 10% for the first 7,500, 12% next 7,500 etc. with an advance of $10,000 over 4 payments. $2,500 upon signing contract, $2,500 when half manuscript is finished etc. Royalties are based on "actual monies received", so that's the wholesale price less returns as I read it.

I think it is a low offer. Frankly, I figured that something of that magnitude would be worth about $60,000, considering the expenses involved. On the other hand, I have done most of the traveling and will do the rest this year. What I don't have is a lot of the details like taxi prices, bus schedules etc.

One friend said I should do the book as a vehicle to get my name known. I don't know if guidebooks are the way to do that or not. You certainly have quite a name in the field. Another said that writing articles would be more lucrative and a better vehicle.

Is their offer ok? Any observations you can give me will be most gratefully appreciated. My idea before this offer was to write small books and self-publish, but I need an investment of about $6,000 to get the cost per book down to where it is reasonable.

Thanks, "Mexico" Mike.

----------------------

Mike,

1. A $10,000 advance is average, but I would hold out for at least 40% of it (better, 50%) before you start the work. You may need the capital. It is common for publishers to pay out the rest as the work progresses, particularly with a first-time author.

2. The royalty rates offered to you are average (10% with an escalator to 12%) for percentage of net. However, your contract should determine very precisely what constitutes "net," and how the books will be sold. If the publisher decides after a year to sell off the guides at cost, you get nothing, whereas if your contract had stipulated cover price you would have to be paid full royalty. "Net" is a slippery term. "Cover price" is an indisputable amount of money. And all royalties are based on sales less returns.

It's instructive to know the publisher's returns policy, and how long they will be permitted. Also, will the publisher withhold a "reserve against returns?" For how long, and when will the reserves be released to you? Find out.

3. I can't tell if this is a low offer or not. In a sense, only time will tell. It depends upon how good a book you write, the market, the way the publisher promotes the book, whether or not there are any bad headlines which dissuade travelers from going to Mexico, etc. On the face of it, these terms sound normal, but one bad clause in the contract can change that. Publishers do all sorts of things these days, some of them quite unethical.

4. Writing a book makes you an instant expert, particularly if the book is in a respected series. It promotes your reputation far faster and farther than a series of newspaper or magazine articles. The very big magazines pay better (I've earned $2 per six-character word), but they only give the work out to writers they know and trust--writers who have already made names for themselves by, say, writing a guidebook!

5. Bottom line: If you like detail, like writing, like Mexico, trust the publisher, get a good contract, and plan to do the revisions to the guide, it can be a pretty good deal. The first edition won't make you much money (if any); succeeding editions may make decent money (but see No 3 above) because you don't have to do all of the writing again, and you'll know where a lot of the info is.

6. Self-publishing can be quite lucrative. Richard Bloomgarten made a good living on his simple self-published books to Mexico because he very smartly set up his own distribution network. But that's another subject entirely.

Hope this helps.

Tom

Guidebook Contract Offer

Travel Writers Sites Ranked by Google

Close Call for Cruise Ship

Written Road Blog - http://www.writtenroad.com

Travel writer and editor Jen Leo share how to break into travel writing via market leads, how to market yourself and editor lists.

Travelwriters.com - http://www.travelwriters.com/

The mission of this site is to be an up to date source of market information, tips on improving your writing, and a guide to the best resources for travel writers on the net.

Travelwriter Marketletter - http://www.travelwriterml.com/

Monthly newsletter for those in the competitive field of travel writing.

Freelance Travel Writing - http://www.FreelanceTravelWriter.com

Learn how to create compelling travel writing features. Free newsletter with tips and travel markets.

Media Kitty - http://www.mediakitty.com

Online information exchange uniting top working journalists and PR professionals in travel and tourism worldwide.

Australian Society of Travel Writers - http://www.astw.org.au

Information and member details of the Australian Society of Travel Writers

Travel Info Exchange - http://www.infoexchange.com/Guidebooks/Guidebooks.html

All about travel information: how to get it, judge its quality, price it, write it, picture it, design it, update it, and communicate it to travelers. How to write a travel guide, resources and an email discussion.

Travel Media Association of Canada - http://www.travelmedia.ca/

A professional, membership-based, non-profit organization of travel writers, broadcasters and industry personnel.

Travel Writing Tips - http://www.travelwritingtips.com

Freelance travel writer Flo Conner provides step-by-step tips and articles to turn your 'Treks into Checks'.

Offbeatrips - http://www.offbeatrips.com

Online freelance travel writing course providing tuition in key aspects of freelance travel journalism, encompassing writing, photography, sponsorship and marketing. Australia.

Travel Writing for Fun and Profit - http://www.writerswrite.com/journal/aug98/philcox.htm

Travel Writing for Fun and Profit, an article by Phil Philcox.

Philip Greenspun's Travel Writing Career - http://photo.net/webtravel/history.html

"How I got started as a Travel Writer", article by Philip Greenspun.

Adventure Travel Writer - http://www.AdventureTravelWriter.com

Editorial advice and how to break into travel writing. Learn about the travel writer's lifestyle.

In Search of Elusive Metaphors - http://www.samexplo.org/mardon.htm

The Art of Travel Writing. Article by Mark Mardon.

Travelwriters UK - http://www.travelwriters.co.uk

A resource for professional travel writers and travel editors.

Travellady Magazine - http://www.travellady.com/articles/article-travelwriting.html

"Everything you Ever Wanted to Know about Travel Writing" article by Madelyn Miller.

00AandEsTravelWriter - http://groups.yahoo.com/group/00AandEsTravelWriter/

How to make a living as a travel writer. Writing discussions and tips. Finding markets that pay. Small email list.

Wanderlust Writers - http://groups.yahoo.com/group/wanderlustwriters

A group for travelers who like to write about their journeys. Post links to your writings about travel.

Travel Writers Sites Ranked by Google

Lonely Planet Veteran on Travel Guidebook Writing

San Diego on Fire

Home Truths From Abroad

BBC2's Foot In The Door series gives eager recruits the chance to get started in their dream job. On Thursday the assignment is travel guidebook writing. Mark Honan, a Lonely Planet veteran with 10 years' experience on four continents, gives the inside story on his job - no time to see friends, no time to laze around on the beach. And people say it's a life of glamour...

Mark Honan

Observer

Sunday June 18, 2000

So you want to be a travel guidebook writer? Most people do. 'You lucky so-and-so,' I've been told countless times. 'Fancy being paid to be on holiday. What a great job.'

Think of the benefits, these travellers tell me. Eating in fancy restaurants. Bedding down in the top hotels. Spending arduous ('ha-ha') days researching the best beaches for sunbathing and swimming. Being treated like royalty because everybody wants a favourable mention in my guidebook.

That's the theory. The reality is there are plenty of hassles too.

Far from being treated like royalty, guidebook writers are an anonymous bunch. Most of us don't declare who we are when we check out places: we want to find out what sort of a deal an ordinary traveller would be offered. In hotels, we invent an excuse to see a selection of rooms. 'I'll be returning in a few weeks with my parents, uncle, long-lost half-cousin and their disabled cat.' That sort of thing.

If we do have to reveal ourselves, the red carpet is rarely rolled out. In Europe proprietors are often suspicious. 'What sort of book? I don't want to pay to be in a book,' they say aggressively. Even when they learn they don't have to pay - in fact, they can't pay - their attitude doesn't soften.

In Germany once, a hotel receptionist refused to let me view any of his empty rooms. 'Show your editor that picture instead,' he said dismissively, throwing me a brochure. In Switzerland, a proprietor was too lazy to tell me the full range of room prices. 'Fine,' I shot back, 'in that case I'm taking you out of the book.' My reward was to be chased down the stairs and out on to the street by a furious, swearing hotel owner.

In Asia, where Lonely Planet is recognised as the market leader, people do tend to fawn over you a little more, provided they manage to discover who you are. (Somehow, in India, everyone seemed to know I was writing for Lonely Planet, despite my denials.) But the odd free beer is usually as far as it gets. Accepting freebies is frowned upon, as we must be scrupulously objective in our write-ups. Accepting payments or discounts in return for positive coverage would mean the immediate termination of any research contract with Lonely Planet.

Guidebook writers have only moderate status within a large publisher. We can rarely keep copyright of our own words. It's the publisher's name that sells the books - the author's name is often relegated to an inside page, or perhaps even omitted altogether (not so in Lonely Planet books: we even get a blurb and a photograph). Rumours circulate that publishers consider authors a necessary evil - specifically 'Lower than a snake's arse,' according to some choice recent gossip.

In the early days of guidebook publishing there was more opportunity for diversity and creativity, especially with a cutting-edge publisher. Nowadays, the market is much bigger and more competitive. Travel books are a standardised 'product'. Each book within an imprint must have the same look, approach and useability. Authors have to adhere to a rigid 'house style'. It's the McDonaldisation of travel destinations. As a writer you can't help but feel disenfranchised.

This has increased the status of editors. They will ruthlessly police our words, dispensing swift justice to anything that fails to conform. Imperious decrees will be issued, containing copious demands for clarifications or background information. Authors must respond to these swiftly, no matter what other commitments they have. Once I arrived in the Solomon Islands, but had to wrench my mind back to Switzerland to deal with a thick wedge of editorial queries and proofs.

Don't count on making your fortune writing guidebooks. Newcomers want to do this job so much that they will do it for virtually nothing, at least at the beginning.

They will endure countless hardships to eke out their meagre budget and track down the information they need. They'll visit plush hotels, test the sweetest-sprung divans, then end up sleeping on hardboard bunks in cardboard shacks. They'll study poetic menus in gourmet restaurants, linger longingly to ask a few patrons how they enjoyed their multi-course feasts, then dine in the meanest roadside slop-shops. They'll check prices for first-class rail and club-class jets, then breathe deep on the clouds of smoke seeping from broken exhausts in battered buses. They'll do it because they enjoy it. Rather, they'll enjoy the first three days of their three-month trip, because it's new and fresh. After that it becomes a grind. We've all been through this rite of passage.

These new writers have quickly found that the so-called glamour has disappeared. They'll console themselves with the thought that once they've got this first book under their belt, they will have their foot in the door. Then they can start making some real money for their next book.

What they soon realise, as they're attempting to negotiate their new project, is that the next batch of wannabe writers is clamouring to write that same book for next to no money, their own 'isn't this cool' rose-tinted glasses as yet unshattered. Thus the one-contract veteran will have to settle for slimmer fees. Another bugbear is the deadlines which are as tight as an ageing swinger's belt. The reason for this is that publishers need to get books on the shelves before they are out of date. I would love to spend four months researching three chapters of India, even at the cost of earning less money per day. One day chilling out on the beach, the next day researching, and so on.

No chance. If it can be researched in two months, I will be given two months minus one week. I will have to work almost every waking hour, seven days a week: researching throughout the day, writing up or organising my notes at night. Travel becomes a joyless logistical exercise, conducted at a relentless pace. I will have to steam into town, check out everything in the guide and line up a few new entries. As soon as this is done I must ship out to the next place, casting wistful glances at the relaxed, time-rich travellers pondering where to have a leisurely beer. I will have nightmares about having my research notes being stolen. My dreams will be invaded by endless investigations of imaginary hotels, restaurants and train stations.

I will return home exhausted, with a backpack bulging with brochures, timetables and price schedules. I will have to forget I have friends I haven't seen for ages. Instead I will retreat to my office until the writing-up is complete. During that time I will fail to recognise the concept of a weekend or office hours. As the deadline approaches my stress levels mount. Every hour I am awake and not working, I will be trying to suppress the nagging thought: 'I could be working right now.'

At last the job will be finished - if I'm lucky, within deadline. I can afford a cou ple of days off now (unpaid, of course), before I start worrying about where my next contract is coming from. Before long I'm back on the road again, wrenching apart the strands that hold my life together in England.

Which heralds the next problem for the career guidebook writer. Taking two- or three-month research trips abroad is great in your carefree early twenties. As you get older and collect more commitments, this gets harder to organise. I am married now and our first child, a daughter, was born last month. Sadly, I know that important stages in her development will happen while I am somewhere else. The career of a guidebook writer tends to be a short one. Within Lonely Planet it is said that writers usually suffer 'burn-out' within five years.

All of this begs the question: if this dream job is so terrible, why am I still doing it?

Because, naturally, it does have its good points too. It's nice that people think I've got a cool job, even if I don't always think it's so cool myself. The research can be exhausting, but there's a genuine satisfaction in finding a place that stands out, and then describing it accurately and evocatively. It's good to be working out there in the real world, instead of being locked up in an office. Then there's the thrill you get when you see your guidebook in print for the first time. And I still love to travel, even if it's for the sake of work rather than for the sake of travel itself.

Perhaps this last point is the key message for wannabe guidebook writers and everybody else. We're out there on the road to do a job, and we can never be deflected from that. Writers who go out there and treat it like being on holiday will end up with just that - an overlong holiday. Plus a blown deadline, withheld fees and no chance of being offered another research contract. Ever.

Lonely Planet Veteran on Travel Guidebook Writing

NWU Report on Pay Rates for Freelance Journalists

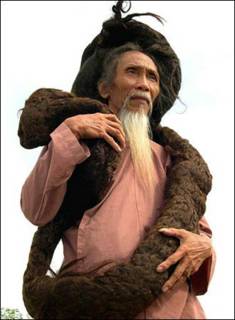

Longest Hair in the World

Report on Pay Rates for Freelance Journalists

Last year, the National Writers Union Delegates Assembly appointed a committee to study pay rates for freelance journalists in order to determine a minimum recommended rate.

Our research was motivated by a strong sense among our members that freelance rates don't provide freelancers with even a moderate income. We believed that rates have not kept up with staff salaries in recent years. We had also heard widespread claims that freelance rates had not gone up since the 1960s. So we set out to see if there was any basis in fact for these beliefs.

In addition to researching what freelancers need to charge per word to make a living, we aimed to put the information into context: Have freelance pay rates increased, stagnated, or decreased since the 1960s? What do staff writers make? What do other college-educated professionals make? How much can publishers afford to pay writers?

We discovered that the situation is even worse than we had thought. In real dollars, freelance rates have declined by more than 50 percent since the 1960s. And while rates have gone down, publishers are getting more for their money.

This report deals only with rates, not rights, but it must be noted in passing that publishers are asking for and getting more secondary rights for the same dollar that once bought only one-time rights. Writers who used to compensate for the poor pay rates at newspapers by reselling articles to multiple markets can no longer do so.

How much do full-time journalists need to charge to make a moderate living?

Freelance writers spend a tremendous amount of time looking for work (researching and pitching articles) and revising. While some articles can be done in a week and others may take three months, for most full-time freelance writers, selling and writing 3,000 or 4,000 words a month is about the best that they can expect to do -- two feature articles or the equivalent in smaller pieces. (This is more than most magazine staff writers write -- which is about 2,500 words a month.)

At this level of output, a rate of a dollar a word means a gross income of $36,000 to $48,000 a year, out of which has to be taken expenses, insurance, and other benefits. This is the equivalent of earning a salary, with benefits, of about $30,000 to $40,000 a year. So for a college graduate working as a full-time freelance writer to bring in even a moderate income that includes benefits, requires at least $1 a word.

The median income of full-time, college-educated workers in the US is around $50,000, plus benefits. So to earn as much as the average college graduate would require somewhat more, between $1.25 and $1.60 a word.

How much did magazines pay in the past?

In real dollars, magazines used to pay far more than they do today. Freelancers' rates have been declining since the mid 1960's in real terms--for more than 35 years. For example, Writer's Market, which reports what magazines themselves say they pay, shows that writers' rates at the top magazines have declined by two-thirds to four-fifths since 1966, far more than the approximately 20% loss in real hourly wages that the average American worker suffered during the same period. Writers' real rates were falling even in the late '60s and early '70s when most workers' wages were rising.

As an example of the generation-long losses, in 1966 Cosmopolitan reported offering $0.60 a word, while in 1998 they reported offering $1 a word. In the meantime, the buying power of the dollar fell by a factor of five. So Cosmopolitan's real rates fell by a factor of three. Good Housekeeping reported offering $1 a word in 1966 and the same $1 a word in 1998- — a full 80% decline in real pay.

Another way of looking at these figures is to translate them into 2001 dollars. In terms of these dollars, Good Housekeeping was paying $5 a word in 1966.

To fully compare these figures with rates actually paid today, one must take into account that that the magazines' reports to Writer's Market underreport rates by as much as a factor of two in general, as demonstrated by the NWU's own ongoing survey of what writers are actually paid by the same magazines. Such underreporting of rates occurred in 1966 as well, so actual rates for Good Housekeeping, in 2001 dollars, may well have been higher than $5 a word.

How much do magazines pay their staff writers?

The average wage for staff positions ranges from $35,270 for news reporters to $45,500 for staff writers, plus benefits, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Based on our examination of largely staff-written monthly magazines, the average staff writer's output is between 20,000 to 30,000 words per year. This means that per-word rates average around $1.60 a word, not including the value of benefits. If benefits are included, this works out to close to $2 a word. (To be conservative, we used the Bureau of Labor Statistics' figure for staff writers. At the actual magazines we surveyed, most staff writers are paid at least twice that, which would mean per-word rates come out to about $4 a word.)

How much can publications afford to pay?

We also compared publication income with words of text published to get an estimate of income per word and to determine what fraction of total revenue is paid to writers. For example, for Discover magazine, 500 pages of ads a year at $50,000 per full-page ad gives $25 million a year in gross revenue. (This underestimates their income, because half-page ads cost two-thirds as much as full-page ads). Since the magazine has one million subscriptions at $25 per year, it has another $25 million a year. (This ignores newsstand sales, which make the total even larger.) Divide by 500 pages of text a year at 800 words per text page and Discover's income is more than $125 per word. Discover pays its writers $1 a word. So they pay their writers less than 1% of their gross income. If they paid them 15% of gross income, the way book publishers manage to and still turn handsome profits, they would be paying at least $19 a word.

The numbers are remarkably similar for Forbes, which also charges $50,000 a page for full-page color ads and also earns roughly the same income from ads as from subscriptions.

In general, advertising and subscription revenues are proportional on a per-word basis to circulation--the more readers, the more income per word. We estimate that publications can afford to pay 15% to 30% of their total revenue to their writers. This means that publications, except for those with fewer than 25,000 readers, can afford to pay $1 a word. This is confirmed by the fact that some magazines listed in the NWU Guide to Rates and Practices as having ad rates under $5,000 a page (the lowest category) did in fact pay as much as $1 a word four years ago, although rates have fallen since then. It also means that writers are being paid no more than 1% to 2% of total income, basically a tenth of what the book publishing industry pays.

For the largest magazines, the gap is even worse. Magazines like Good Housekeeping and Women's Day with ad rates of $200,000 a page and more and as many as eight million readers are earning something like $500 a word. Yet they pay freelancers $1 to $2 a word, less than 0.5% of revenues. If they paid the writers 15% of revenue, freelancers would be getting $75 a word at these publications.

What about newspapers? The New York Times takes in about $40,000 per ad page or about $2 million per issue, about comparable to Discover, Forbes, and Good Housekeeping. The Times metro edition hits about a million readers. With $1 million or more in subscriptions per issue, not counting newsstand sales, and 30 pages of text in a daily edition, this works out to at least $38 a word. So at 15% of income, the Times could afford at least $6 a word, not the 30 cents to a dollar it normally pays freelancers.

Thus a minimum rate of $1 a word is no hardship for publications and will be a first step to recovering the ground writers have lost over the past thirty five years.

NWU Report on Pay Rates for Freelance Journalists

Lonely Planet and Globalization

Burma Postcard

All the Lonely People

Globalization helped grow Lonely Planet Publications.

Now globalization helps it ship local jobs overseas.

BY KARA PLATONI

Workers must hit the road.

For years, the Oakland-based staff of Lonely Planet Publications cranked out much-beloved guides that help travelers figure out how ferry service works in Alaska or where to buy soccer tickets in Costa Rica. And for years, things were good. Buoyed by the rising tide of global commerce, international boundaries blurred, worldwide travel boomed, and people hankered to get farther and farther off the beaten path. Lonely Planet grew by making the planet a bit less lonely.

By growing more than twenty percent a year for a decade, the privately held company was becoming the world's largest independent travel publisher, with more than 650 titles in print. At its peak, Lonely Planet employed about 550 people worldwide, a quarter of whom were the designers, cartographers, editors, and new media staff based in Oakland.

As the company grew, so did its ambitions. Once fondly regarded as a producer of backpackers' bibles, Lonely Planet began aiming for a wider audience. The company spun off a host of products including videos, language tapes, road atlases, coffee-table books, and digital travel guides. It made plans to produce television broadcasts under the moniker "LPTV." It also ventured into multimedia, launching a Web site, an Internet bulletin board, and a phone-card service. Along the way, it developed a reputation for being the nice guy of travel publishing, a company that donated some of its profits to charity and urged trekkers to be respectful of the environment and culture of the places they visited.

But now the global business tide that once lifted Lonely Planet's fortunes is washing back out. Last month, for the first time in the company's nearly thirty-year history, Lonely Planet announced that it would lay off fifteen percent of its global workforce and move all book production back to its original base in Australia, where the Australian dollar is worth about half its US counterpart. The vast majority of those cuts will come from the Oakland office -- about seventy people -- and be staggered from March through July.

Despite early news coverage that blamed Lonely Planet's layoffs on the post-9/11 travel slump, company executives have made it clear that slowing revenues, the need to pay off bank loans, and pressure for the company to develop its first-ever long-term financial plan made changes necessary well before September.